Transportation experts often talk about the potential of Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) to solve the “last mile problem.” What they usually mean is the potential for people to use TNCs in combination with transit to reach key destinations just outside the reach of transit. Many of the collaboration pilots around the country between TNCs, transit agencies, and employers are aimed at addressing the last mile problem of work trips, particularly to suburban locations that lack safe pedestrian and cycling connections to nearby employment centers. In addition to making it easier to hire and retain workers who can’t afford to or don’t want to drive to work, these programs may also help employers and cities avoid the expenses that come with providing parking. For example, Summit, New Jersey has been running a program since 2016 that subsidizes TNC rides to the city’s train station to avoid expanding the station’s parking lot.

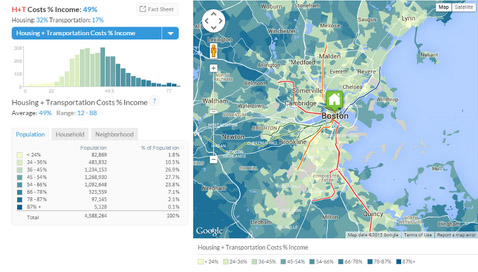

Reducing parking demand, particularly in areas near transit, has numerous benefits for communities and individuals. Reducing parking needs in neighborhoods can make market-rate housing more affordable and increase the number of subsidized units provided in a community. CNT has documented the relationship between the cost of parking and the cost of housing through the report Stalled Out and parking tools in Washington, D.C., California, and King County, Washington. In the Chicago region, the cost of constructing a single parking space can vary between $4,200 in a surface lot to $37,300 in an indoor, underground parking garage. When an infill development provides one parking space per unit, it may see a 25% decrease in the number of units provided on site when compared to a development without any parking at all. For projects running on affordability subsidies, this reduction of units greatly impacts a project’s financial viability.

Stalled Out: How Empty Parking Spaces Diminish Neighborhood Affordability

Stalled Out: How Empty Parking Spaces Diminish Neighborhood Affordability

Explore the relationship between unused parking and neighborhood affordability.

Reducing residential parking demand is more challenging than reducing commercial parking demand because commercial destinations tend to be the places that are most expensive and least convenient to park, and because a household can only eliminate the need for parking at home if they eliminate a car. There is evidence that TNCs are reducing the need for parking in commercial centers. A recent study in Denver found that ride-hailing replaced driving trips and could reduce parking demand, particularly at destinations like airports, event venues, restaurants, and bars. However, research on the effect of TNCs on residential parking is limited. Some survey evidence suggests that people who use TNCs in addition to transit and other modes, like carshare, scooters, and bikeshare are more likely to get rid of a car or avoid buying a second car. However, census data does not yet show a significant decline in auto ownership anywhere in Chicago, or in other cities with significant numbers of TNC trips. Some analysis shows that the number of “car-rich” households in urban areas is increasing.

Making it easier to live in a car-free or car-light household, and capturing the affordability benefits of reduced parking demand, requires solving a different kind of last mile challenge from the one most TNC pilots have focused on: making it convenient and affordable to reach all kinds of destinations, including work, play, shopping, medical appointments, and childcare, without owning a car. TNCs have a potential to be part of this solution, particularly for people living in places where commute patterns are well-served by transit, but where other trips—grocery runs, doctors’ appointments, are less easy to accomplish this way.

Using TNCs for this kind of occasional travel is significantly more affordable for the average household than relying on TNCs for daily commutes. Based on information about vehicle cost data from the H+T Affordability Index and TNC cost data from the City of Chicago’s public dataset, CNT estimates households can come out ahead by replacing a car if they add fewer than 2,000 miles of TNC travel per year, or 5 miles per day. This is far shorter than the average commute distance in the Chicago region.

More research is needed to identify places where TNCs are most likely to be an affordable last mile solution, and develop policies that can make communities more affordable places to live and work. CNT is committed to continuing this work in 2020 and the years to come.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships