In collaboration with the Institute for Sustainable Communities, CNT analyzed equity of access to smart mobility in Chicago and nine other cities across the country. The purpose of the report was to explore disparities in access to transportation options that incorporate technology, support a clean environment, and enhance access to opportunity. CNT calculated measures related to accessibility, employability, livability, and mobility, broken out by race, ethnicity, and income. Check out the full report here.

Among the measures we calculated was availability of Transportation Network Companies (TNCs), bike share, and car share. We should note that availability of service isn’t the same as access. There are many reasons why someone might not use a transportation option that is available to them, including cost, safety, child-friendliness, disability accessibility and other factors. However, it is impossible to use a service that is not available in your community, and measuring availability is one measure assess how equitable service is.

Unlike the analysis in the other blogs in this series, our accessibility analysis looked not at ridership data provided by the city, but another source, the information provided by Uber and Lyft on how far away the nearest driver is to a given location at a given time. This is the information you see on Google Maps, TransitApp, or within the TNC companies’ apps themselves.

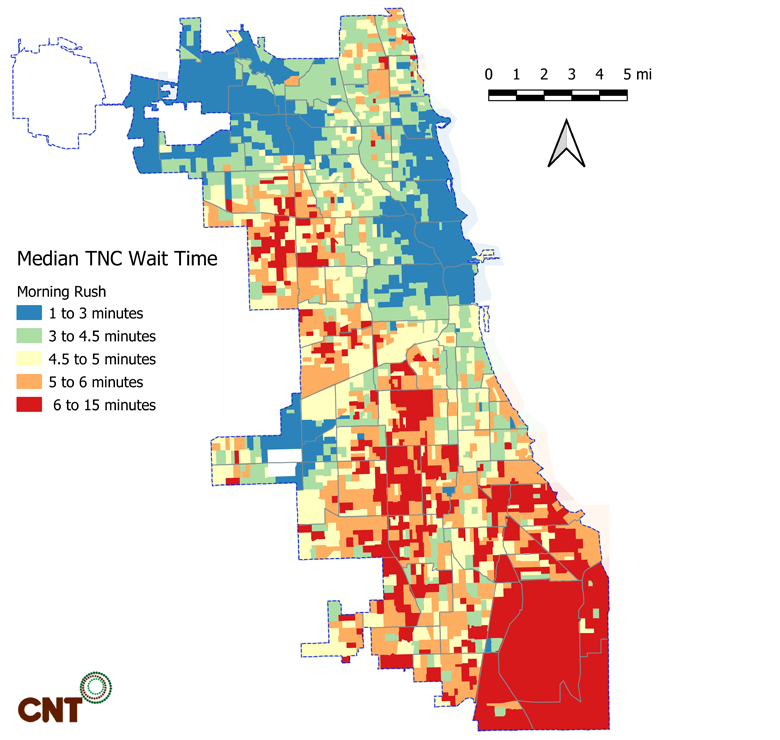

To assess TNC availability, we looked at wait times across the city of Chicago for nine consecutive days during the month of February in 2019. Other than at O’Hare and Midway, which have some of the longest TNC wait times in the city, wait times were shortest in the same areas that see the highest TNC use, in the city’s North Side neighborhoods and along the O’Hare branch of the CTA Blue Line. They were significantly longer on the Far South Side. This disparity doesn’t appear to be a function of where drivers live. The city’s TNC1 dataset provides information on the number of drivers by zip code, and there are relatively high concentrations of drivers on the South Side and in the South Suburbs.

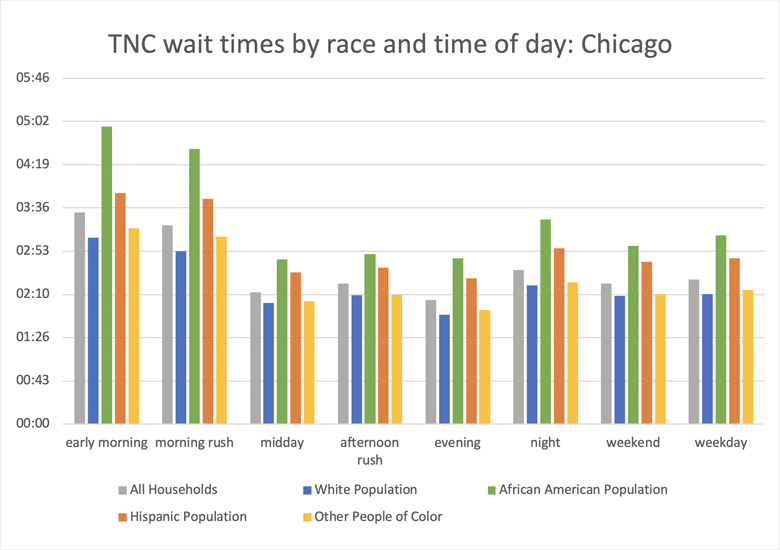

In public transit service, low ridership leads to service cuts which leads to declining ridership. This negative feedback loop is also apparent in TNC use. Disparities in wait times may not be intentional on the part of drivers or mobility companies. It is likely that longer wait time is one of the factors that limits TNC demand in these neighborhoods, which in turn may result in fewer drivers and increased wait times. Other factors, such as cost may be a bigger factor than wait time in people’s mode decisions.

Chicago’s persistent patterns of racial segregation combined with disparities in TNC wait times creates substantial racial disparities in TNC availability. CNT used American Community Survey to estimate the average wait times residents of different races would experience when hailing a ride from their homes, and found that Black and Hispanic Chicagoans experience substantially longer wait times than White Chicagoans. In fact, these disparities were the largest of all the cities we studied. These racial disparities are particularly pronounced in the morning and persist even when we look only at households above 200% of the poverty line.

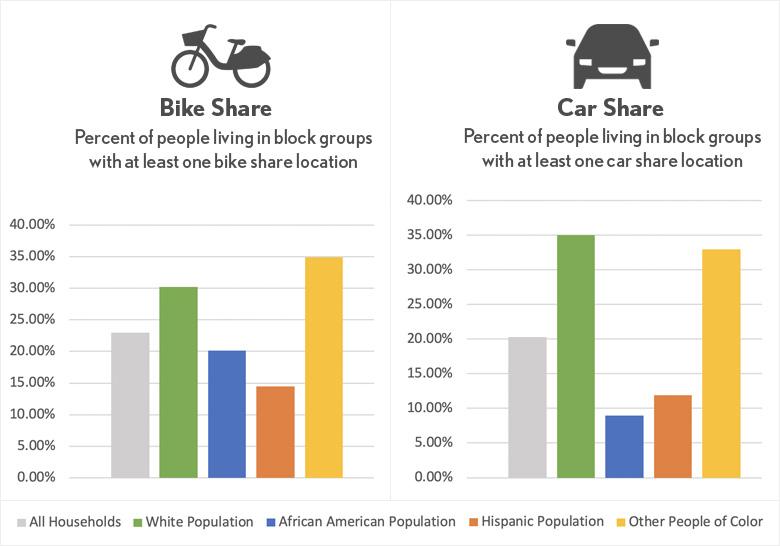

TNCs aren’t the only emerging mode that has disparities in access by race and income. Bikeshare and carsharing services, too, are more prevalent in predominantly white and higher-income neighborhoods.

It is important to embed measurement of equity into evaluations of all transportation options, and into agreements with private companies offering transportation services. For example, the recently renegotiated contract between the City of Chicago and Lyft to operate the Divvy system includes expansion of the Divvy for Everyone program and a pilot of an adaptive bikeshare program, as well as other performance and equity targets. The recently-completed e-scooter pilot program also included requirements that half of the scooters start the day located in lower-income priority areas. Getting these performance measures right, and monitoring them going forward, will be critical.

1The City of Chicago refers to TNCs as TNPs (Transportation Network Providers).

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships