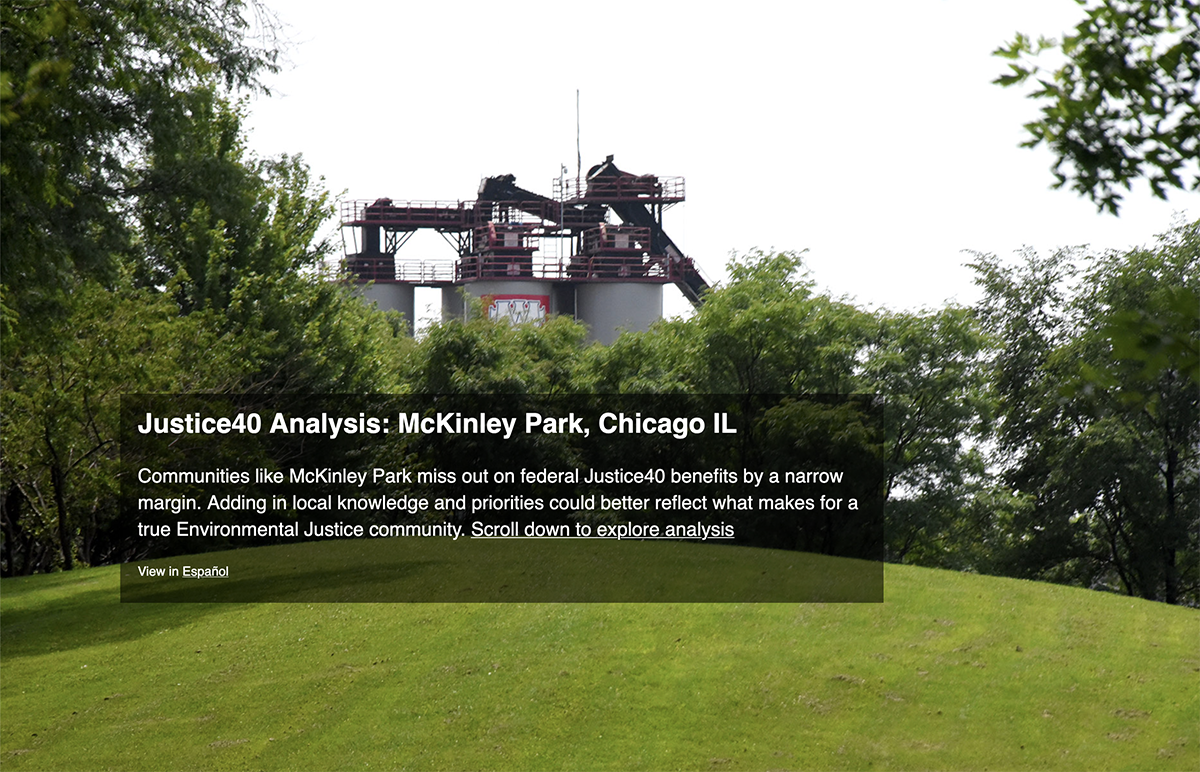

Communities like McKinley Park miss out on federal Justice40 benefits by a narrow margin. It doesn’t have to be that way.

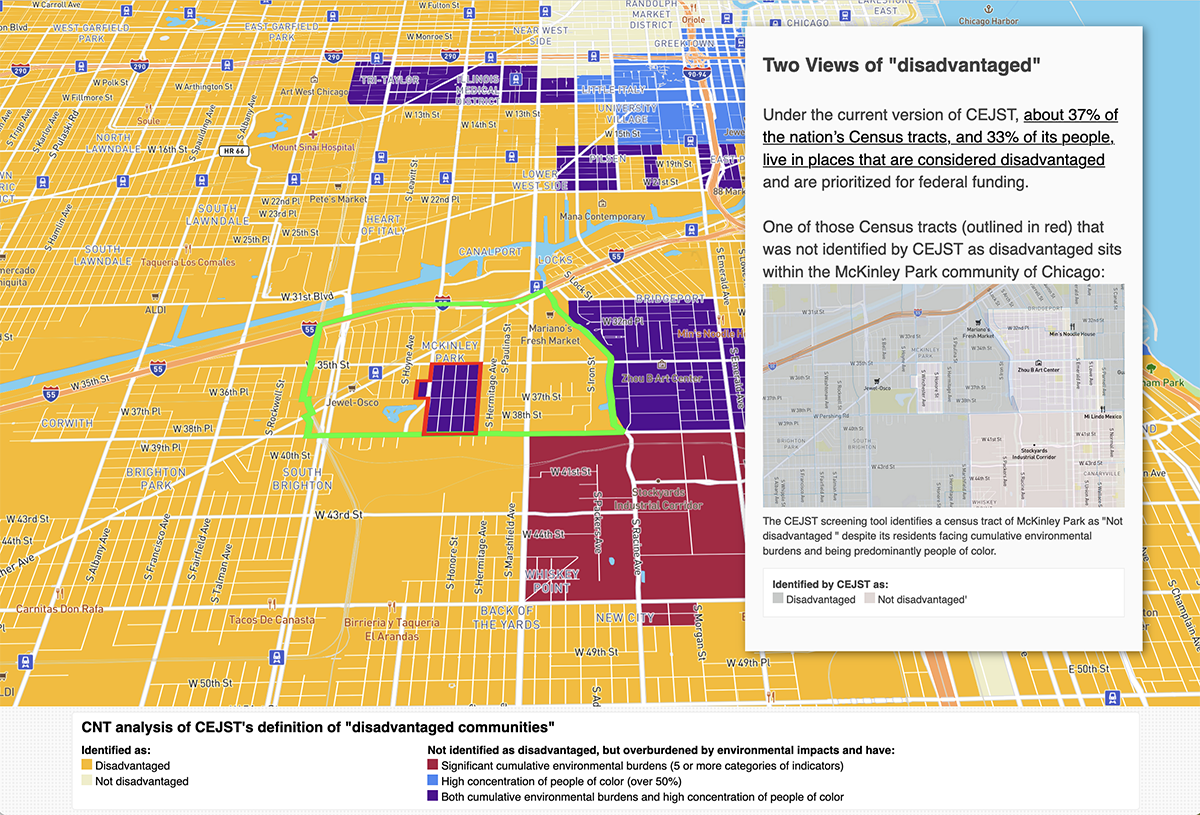

The Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) aims to identify “disadvantaged census tracts” for prioritizing federal funding and informing the national Justice40 initiative, but we wondered – are there instances where the tool fails to identify communities that residents and organizers on the ground know are overburdened by pollution?

When CEJST was first released in November 2022, community organizers at Neighbors for Environmental Justice (N4EJ) immediately noticed that a census tract in their home community of McKinley Park in Chicago was not identified as disadvantaged, despite being across the street from a hot mix asphalt plant, MAT Asphalt. This led to N4EJ and CNT teaming up to explore why this census tract was left out and how authentic community partnership would maximize the success of Justice40.

McKinley Park is a strong, working-class community on the southwest side of Chicago, that historically was home to iron, steel and meatpacking industries. About 25% of the neighborhood is still dedicated to manufacturing and industrial uses, including MAT Asphalt, which has been operating on Pershing Avenue since 2018. Since its opening, residents have filed hundreds of complaints related to air pollution, odors and truck traffic to the Chicago Department of Public Health and the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency.

Why then, is the census tract across the street (17031590600) not identified by CEJST as “disadvantaged,” despite facing cumulative environmental burdens?

In this case, the reason is because it narrowly misses CEJST’s adjusted low income threshold, measured using the percentage of individuals below 200% of the Federal Poverty Line. Because of this, the tract is excluded, despite the fact that it is:

- Experiencing poverty that just isn’t captured by the measure used by CEJST. CEJST requires a tract to be above the 50th percentile of individuals below 200% of the Federal Poverty Line to qualify as “disadvantaged” and this tract is at the 47th percentile. However, it would qualify if the CEJST instead used the area median household income (AMI) as its measure of poverty -- this tract is just 64% of AMI.

- Facing significant cumulative environmental justice burdens. Looking at all census tracts across the country, this tract exceeds the 90th percentile on 5 of 8 environmental and climate indicators used in the CEJST, including diesel particulate matter exposure, proximity to Risk Management Plan (RMP) facilities, and projected flood risk. All five tracts surrounding this one do meet the CEJST definition of “disadvantaged.”

- Located next door to a known polluter. This tract is located right next door to MAT Asphalt, which was built in 2018 without public notice or completing the required Environmental Justice review process. This meant that there were no public meetings, no outreach to community groups and no information shared publicly in advance. New industrial developments like this, especially without due process, create new environmental hazards that then aren’t picked up by national datasets until harm to communities has already happened.

- Home to 86% people of color. CEJST does not include race as a factor in its categorization, despite evidence that environmental racism is closely linked to all of the indicators highlighted in the tool.

Methodological limitations and nuances in federal datasets mean that an index like the CEJST will never get it 100% right. That’s why it is so important for the Council for Environmental Quality (CEQ) to partner with community organizations like Neighbors for Environmental Justice to take lived experience and local knowledge into account.

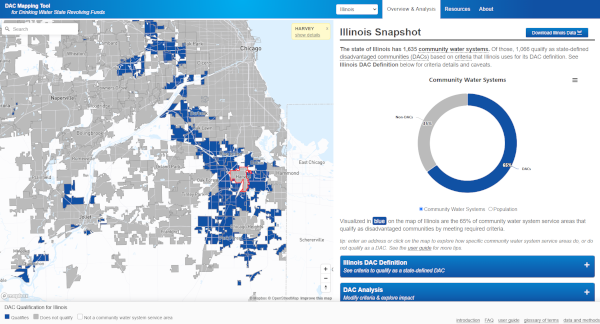

If the CEJST had an option for communities to self-designate census tracts that they know are facing disproportionate environmental burdens, instances like this one would be avoided. The Illinois Solar for All initiative, which prioritizes funding to environmental justice communities identified by the U.S. EPA tool EJ Screen, allows communities to apply for designation by submitting a wide variety of data sources including expert testimony, citizen science reports, evidence of community organizing around an issue, and historical events.

Community knowledge should be held in equal value to quantitative data, and by doing so, we can ensure that the CEJST truly does meet its goal of bringing justice to those living in the nation’s most burdened communities.

Read more in CNT and N4EJ’s StoryMap at: https://justice40.cnt.org/mckinley-park

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships