A food desert is commonly defined as a neighborhood area more than a mile away from full-service food access.

First, a little context: I am a Black female millennial who rents on the West Side of Chicago. Grocery shopping is the only form of shopping I enjoy, I engage in it every other day. My parents moved me to an auto-oriented suburb when I was very young. Without anyone telling me it was so, I believed that when I saw a person walking they did so because they were destitute or mentally ill. For reasons I was too young to fully understand, it was ingrained in me to believe that walking places was unnatural and unsafe (more on this stigma later). After living a few hard adult years in my middle-class suburban community without a job or a car, I made the decision to move back to the West Side in search of a smaller carbon footprint, rapid transportation to my job, activism, and everything else. I found an apartment a half mile away from two CTA el lines: the blue line to the south, the green line to the north. I have walking access to three major bus lines going in all directions. If there’s no Tomfoolery going on, my commute downtown occurs in 30 minutes, because my neighborhood is transit rich.

I ride my bike (which carries the same stigma, as walking) to work, the train, the grocer and any other place I can sneak off to. I say sneak because I am constantly told (fussed at) that this practice is foolishly unsafe, unhygienic, and that my “Black card” will eventually be revoked if I continue. If I had a dollar for every time someone tried to take my card… I ride my bike because I love the environment, I’m cheap, and I otherwise refuse to exercise. With an understanding of my perspective in mind, I have decided to write a series of blogs to analyze the higher costs Black people pay to eat, entirely though the observations I have made my whole life, as an urban planner and as a Black person.

I ride my bike (which carries the same stigma, as walking) to work, the train, the grocer and any other place I can sneak off to. I say sneak because I am constantly told (fussed at) that this practice is foolishly unsafe, unhygienic, and that my “Black card” will eventually be revoked if I continue. If I had a dollar for every time someone tried to take my card… I ride my bike because I love the environment, I’m cheap, and I otherwise refuse to exercise. With an understanding of my perspective in mind, I have decided to write a series of blogs to analyze the higher costs Black people pay to eat, entirely though the observations I have made my whole life, as an urban planner and as a Black person.

It is my hypothesis that three factors have combined to create the environment in which food deserts persist in the Black community, they are the Black perspectives on health and commuting, and the consequences of “integration”. Within the Black community “healthy” is a very subjective term. A belief that healthy food is expensive food in combination with a lack of knowledge about what healthy really is, a lack of full-line grocery access, and a lack of cooking ease has given my people an excuse to maintain extremely processed, sugar, fat, and salt laden diets. Too many of us think, “this is just the way we eat”, not making the connection between our diet and health issues, until it is too late. When we are young, we accept health issues to be “in our genes”, resolving to enjoy our young healthy bodies while we can. That fact that our health care system is reactive rather than preventive is an overall American public health issue, but its silence on preventative care is especially destructive to Black health, as highlighted by COIVD-19’s astoundingly disproportionate Black death toll.

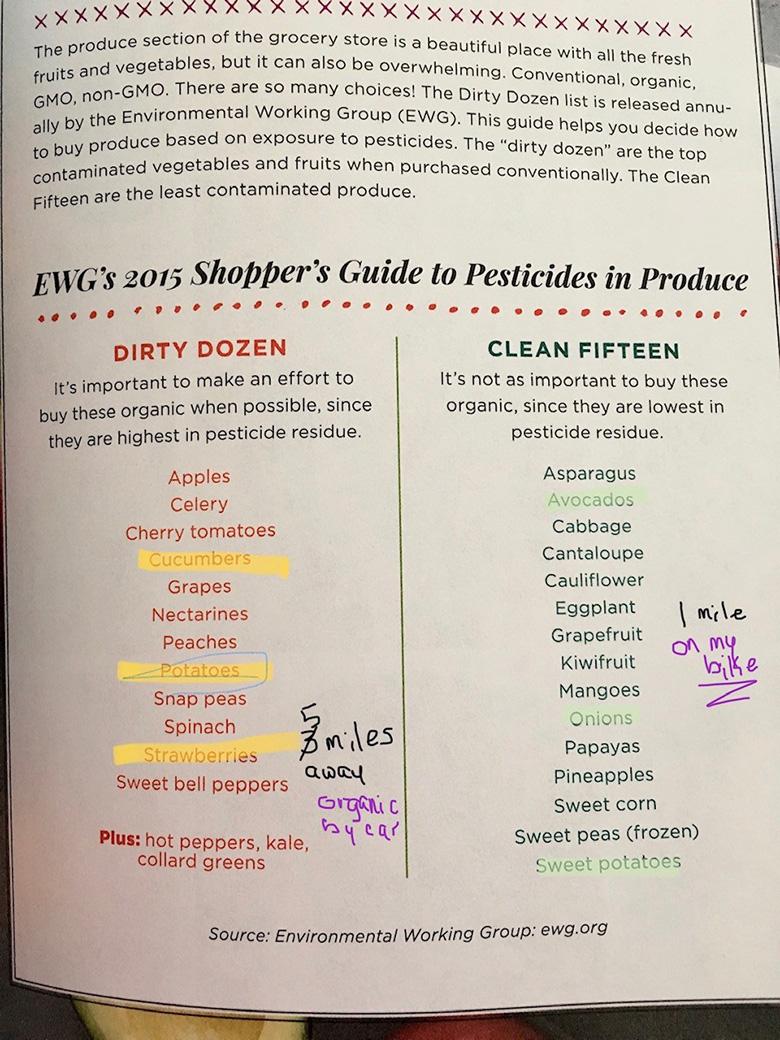

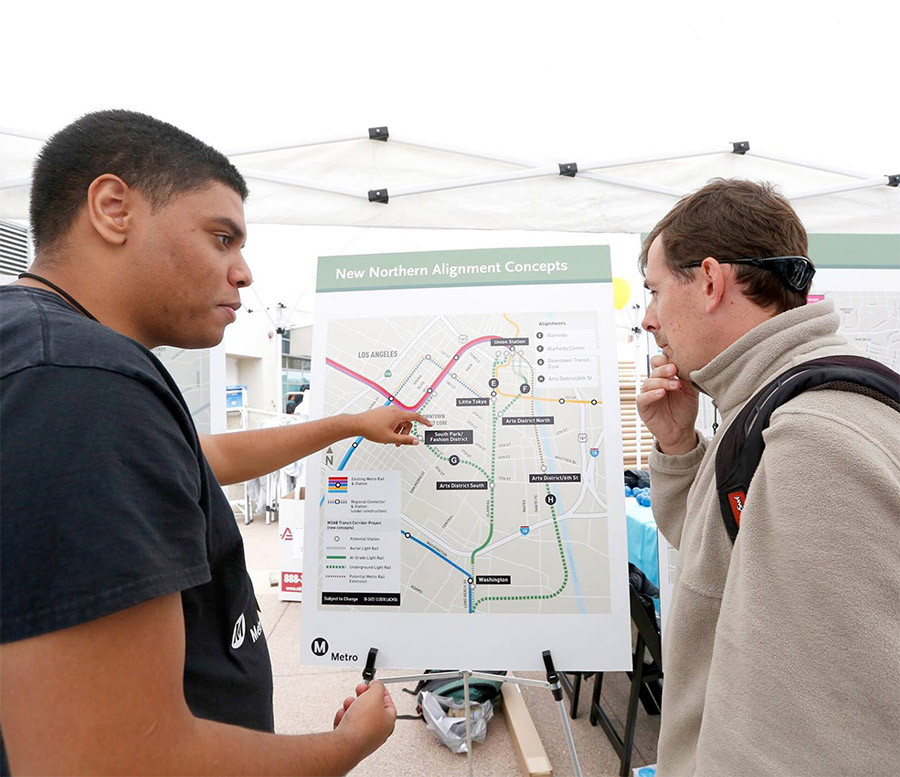

Living in range of multiple possible transit-oriented developments it would seem that I too would have many options to shop in place, but I don’t. The nearest grocery stores are at least 1.8 miles away. The store to the east is a national discount grocer that seemed to rise from the dust during the Great Recession. With more notoriety and popularity amongst middle class folk, the grocer met the demand to offer more fresh produce, fresh meats and health conscious foods. Sadly, this is the only location that closes at dusk, nearly two hours earlier than its siblings. My neighbors with regular 9-5s race against the sun to get that much needed organic salad mix, but the store has been in this admittedly rough location for decades. The grocer to the west is a small local family-owned chain known to many as the “last resort”. The service is decent, there’s a full line of produce and adequate options, but prices are at convenience store levels and the food quality is inferior. This store closes just after dark and has been in the community for years.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships