Beyond all mainstream Obama-induced beliefs, structural racism is alive and well in this country. This type of racism hasn’t even taken a day off. Racism rears its head in many ways, but one of the ways it silently expresses itself is under the narrative of integration. Our ancestors fought hard and persistently to grant us all the right to live and shop wherever we wanted, but the result behaves more like assimilation than integration. Integration is the unification of two or more things. In economic terms, this would mean that retailers would spread themselves across various zones based solely on their consumer market and profit margin. In simpler terms, economic integration means the equal exchange of goods and services.

Under the current integration paradigm, retailers can now explain by using made-up “statistics” (aka stereotypes) and “data”, why a whiter location is a better location for their profit margins. These retailers are furtively designing retail that forces Black people to cross into White-majority communities to patronize White/mainstream businesses, while white people must rarely do the same, if ever.

I believe that retailers forego Black neighborhoods for three reasons:

- Retailers don’t want to cannibalize themselves.

- Retailers know Black people are accustomed to ‘some struggle’ and no longer think to complain about it.

- White people won’t quietly travel as Black people do every day, resulting in the potential loss of white consumers.

My evidence is my lived experience. I have moved several times in my life, but I have always lived in Black communities, and I have always been forced to travel great distances to buy healthy food. When I lived in an upper middle-class Black community, I had to travel at least three miles for quality food. Now that I live in a low-income Black community, I still travel the same distance for equal service. In my world, neither income nor density has made a difference in my grocery journey.

In my final example of observed disparity, I will look at the shuttering of Dominicks. This popular grocery store was a Chicagoland staple for nearly a century. Though some complained of higher prices, Dominicks could be found in every neighborhood type. In 2012, when the chain announced it would be going out of business, giant grocers around the region opted to take over the massive stores and their customer base within a year; well at least they did in white neighborhoods. In Black neighborhoods, officials begged and bartered to keep their communities from becoming deserts, to no avail. Some got family owned grocers that couldn’t really manage the store volume, while others still lie empty. More excuses rained down about why some stores made the cut and others did not. Grocery stores are often the anchor of shopping districts, so a community’s inability to retain the sales tax of its residents is not only a loss in grocery sales taxes, but also the sales tax of all other retailers and small businesses who need a grocery anchor to survive. Less money coming into a community means less money to support that community especially in a time of crisis.

Here are a few ideas I have as remedies to this issue:

- The creation of policy that prohibits grocers from clustering in one area while completely forgoing or even abandoning entire neighborhoods.

- The creation of farmers’ markets and produce pop-ups that locate within the food desert and occur on a regular schedule.

- The creation of urban agriculture.

While this would only be a solution during the growing season when travel is already less burdensome, it is cost effective for those who are physically capable, knowledgeable, and have the time. My generation has been purposely disconnected from the land because of our parents very intentionally trying to prove that they were more capable than the physical labor many of their parents had to engage in to survive. To be clear, my grandparents’ generation were farmers and were the first to enter the industrial age by being a part of the Great Migration. They raised their children in an urban atmosphere, encouraging them to go to school so they could work smart, not hard. Slavery forced us all to be the descendants of farmers. A legacy that should have made us horticultural experts has instead created a desire to separate ourselves from the many stereotypes that still plague us. In addition to the racism and discriminatory housing practices that has prevented us from being landowners, we have lost and devalued the horticultural skills that could supplement our self-sufficiency.

In conclusion, the fault of the unhealthy Black diet does not completely belong to racism or food deserts. In the age of information, we must all take responsibility for our diets and complacency with businesses that will not locate within our neighborhoods. A grocer within a neighborhood allows everyone to access their essential needs on foot or bike, free of excess charges or increased viral exposure. The proclivity of food deserts in Black communities has proven to not only be an economic strain, but also a massive public health issue in a multi-faceted way. COVID-19 has changed the threat we all face with using public modes of transportation. Yet those without privileges such as paid grocery delivery, bike racks, cars, and even short bus routes to-and-fro will cause many to experience COVID-19 in a much more stressful and terrifying manner. Those without the privilege of neighborhood grocers will have to really consider the true cost of an apple or kale.

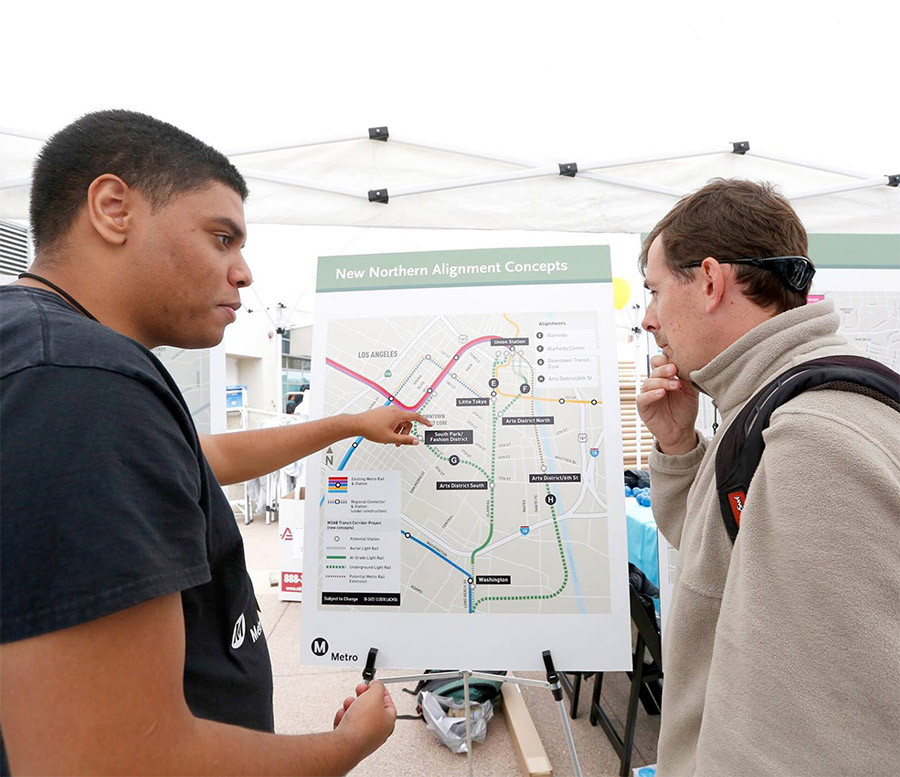

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships