Over and over again we hear that infrastructure in the U.S. has a terrible report card and millions, billions, even trillions of dollars are needed to fix it. Discussed less, however, are the benefits of investing, in particular to upgrade infrastructure beyond the replacement of 100-year-old pipes. We also don’t hear about the high costs of pursuing business as usual—what are we losing by continuing to do things the same way, rather than adapting to changing local needs with systems innovations?

The CNT Great Lakes Water Infrastructure Project had its first webinar March 1, 2018, and our two speakers did an excellent job of looking at water systems needs in the larger community context.

Mark Reiner, PhD, Co-Founder, Technical, and Financial Lead at WISRD, discussed the importance of not thinking of water infrastructure in a silo. He noted that communities are required to complete Hazard Mitigation Plans to receive certain types of FEMA funds, but the guidelines for those plans do not include water infrastructure failure as a hazard.

We know that a community without a safe, reliable water supply is certainly facing an emergency, yet our planning and investments don’t always reflect that. For example, the January 2015 Genesee County, Michigan Hazard Mitigation Plan, which included Flint, MI, discussed dozens of possible hazards for the community. The document identified the potential for water treatment to be interrupted by a power outage and the importance of infrastructure maintenance, but did not mention Flint’s aging lead pipes—a hazard that was by that time already creating a severe public health crisis. Three years later, Flint residents are still using bottled and filtered water.

Just as we need to better coordinate our emergency and infrastructure planning, we also need to coordinate across infrastructure types. Reiner pointed out that we can avoid unnecessary costs by looking at the infrastructure on any given block as a bundle—if a bridge is failing, the water pipes that run along it are at risk; if we are digging a trench for broadband, best practice says we should coordinate with water and sewer utilities to avoid the extra costs of opening the street again a year later.

Kasey Faust, PhD, Assistant Professor at the University of Texas at Austin, talked about potential cost savings and service improvements when infrastructure is adapted to a changing city. This is important for communities like Buffalo, NY or Gary, IN that have half the population they did in the 1950s and 1960s.

Faust pointed out that capping off unused water pipes in areas that have experienced a loss of residents can create many benefits—preventing water from sitting in pipes too long, maintaining water pressure, and driving down maintenance costs by reducing the system footprint. Yet, Faust said, today’s policies are growth-centric. We need make changes to accommodate a decline in population in a community.

Without innovations in the way infrastructure is designed and financed, the cost of improvements will continue to show up as higher bills, increasing the burden for those who can least afford it. The risks include water shutoffs, associated health problems, or worse. When we expand our thinking beyond the cost of water infrastructure investments and consider the broader community benefits of doing things differently, we can start to see increased buy-in for water systems innovation. Our next webinar on March 29 will address a related topic: Non-revenue water, otherwise known as water loss or leaks, is a costly element of our water systems today, and tackling it can be part of a holistic water package that frees up resources for other improvements.

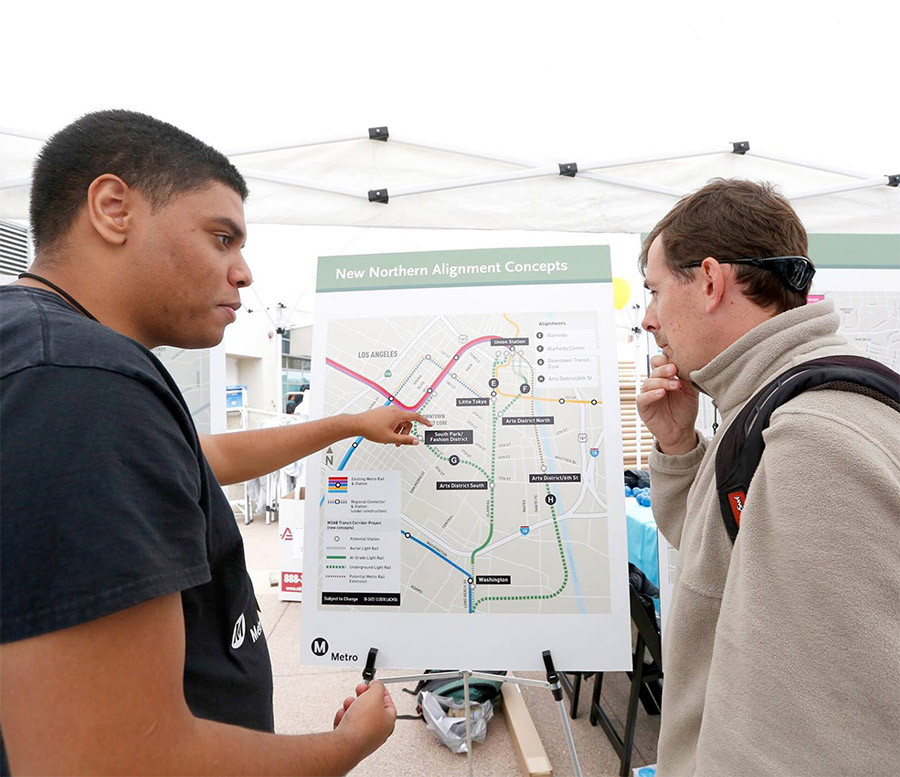

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships