I recently had the honor to sit down with Ben Brown from PlaceMakers to talk about Community Affordability in the PlaceMaker’s blog “PlaceShakers and Newsmakers” CNT has had a long relationship with PlaceMakers, a planning and design firm that works in the United States and Canada. Ben and I spoke about affordability and place, in advance of the Congress for New Urbanism 2018 Conference to be held May 15-19, 2018. Follows is the beginning of Part II of our conversation about Community Affordability. You can read the entire blog on PlaceMaker’s website

Ben Brown, Q: Lots of what we talked about in Part I of this interview was about the connection between community affordability and location efficiency. You make the point that to realize maximum social and economic benefits from policies designed to close the affordability gap, redeveloping in existing, close-in neighborhoods where infrastructure already exists, is essential. That’s also where the politics get complicated.

We saw this recently when African-American community leaders pushed back against President Barack Obama’s Presidential Center in your home town of Chicago. I think we can imagine developers elsewhere saying something like this: “If one of the most revered African-American leaders in the world runs into trouble with community activists because of a plan to bring new development into their neighborhoods, what hope is there for everyone else?”

Scott Bernstein, A: Characterizing the pushback that way misses the context that developers, including the former president, should have been aware of and planned for. But the experience still provides some helpful lessons for the rest of us.

What Obama’s foundation is pushing is part and parcel of a development plan by the University of Chicago and the City of Chicago. Leaving aside the design of the campus itself, the proposal is to relocate a current highway through Jackson Park in exchange for permission to expand both Lake Shore drive to the east and Stony Island Avenue to the west. For many, including me, the evidence is weak that the surrounding neighborhoods will get the economic benefits from investing several hundred million dollars in highway widening along the lakefront and further channelizing a boulevard. Amplifying those suspicions are memories that stretch back to the last century when previous Stony Island “improvements” done to link the lakefront to the broader Interstate system built in the 1950s and 60s wiped out hundreds of locally owned stores and residential buildings.

A local coalition’s efforts to get President Obama’s foundation to sign a community benefits agreement have been re-buffed, with the foundation making the lawyerly argument that it doesn’t represent the other two partners and can’t unilaterally commit to such an agreement. While that may be somewhat true, the response seems tone-deaf and only escalated the anger. It’s the sort of thing that can happen when there’s a lack of transparency in planning and entitlement and a lack of institutional memory.

Q: In this case, what might institutional memory tell us?

A: Recently, I was looking at a copy of a 1947 Chicago Tribune headline, “City Plans Superhighway through Jackson Park,” and a 1956 Daily News headline, “Southeast Side Faces Big Traffic Problems.” warning that new interstate highways being completed would dump hordes of travelers into town unless we make better use of the public realm – that is, Jackson Park serving surrounding African-American neighborhoods — to accommodate traffic growth.

Both the 1909 Plan of Chicago and the follow-up Chicago Plan Commission studies were obsessed with being prepared for “motorization” and the need to interchange such traffic with, for example, Indiana and Wisconsin. The 1929 Outer Drive Plan was intended in part to meet this need. At the time, the concept of limited access highways was only a decade old, itself an outgrowth of plans to bridge disconnected parts of a “three-sided town” defined by the branches of the Chicago River. Eventually plans were drawn for a highway through Jackson Park. Needless to say, that vision evolved without a lot of concern for or input from neighborhoods likely to be most affected. Despite national-news-generating protests, including residents chaining themselves to trees, the road was pushed through. What we know now from analogous efforts in almost 100 cities around the world is that these capacity additions induce traffic and reduce property values – but also that it’s all reversible.

Q: So the hordes of motorists didn’t materialize. Is there a better option?

A: Estimates of the daily traffic volume through the road in the park range from 20,000-30,000 vehicles per day, less than 10 percent of the average volume carried on Interstate 94 to the west. The additional volume of expected visitors to the Obama Center is 200 visitors per hour, or 2,000 in a 10 hour day. The location of the Center at 63d and Ashland was served by a branch of the CTA elevated rapid transit, torn down in 1998.

Two options that would have community support to removing the highway from the Park and adding capacity are: (a) building an overpass and underpass combo, the former for pedestrians (an idea invented by Olmstead, which made Manhattan’s Central Park feasible); and (b) simply removing the highway and focusing any capacity additions on human scale transportation alternatives such as pedestrian, transit, car-share, and bike-share alternatives.

Q: What’s next for the Presidential Center proposal?

A: The application to the Chicago Plan Commission will be reviewed on May 17, and their recommendation forwarded to the Chicago City Council this summer. Various environmental impact and historic preservation reviews are being conducted. The Mayor has taken leadership among cities internationally to have Chicago meet the Paris climate accord; good, inclusive urbanism can contribute to that goal.

The question for this project and for others like it: Is it really unreasonable to ask for routine priority-setting for a multi-bottom-line community benefits plan? Without the disinvestment aided and abetted by the larger highway investments and the redlining practices of earlier decades, those south side neighborhoods could have turned out much better for everyone.

Q: The takeaway for engagement efforts?

A: Context counts. The history of a place and the power struggles to control it have to be taken into consideration in planning. You have to understand and anticipate what’s informing the perceptions of people affected by a plan. And you’d better be prepared to demonstrate the likelihood of the benefits you promise in ways that overcome the suspicions history imposes.

Interested in reading more? Read the entire blog on PlaceMaker’s website to hear the rest of Scott’s comments on how CNU members have played a role, and what paths forward show promise, and what doesn’t.

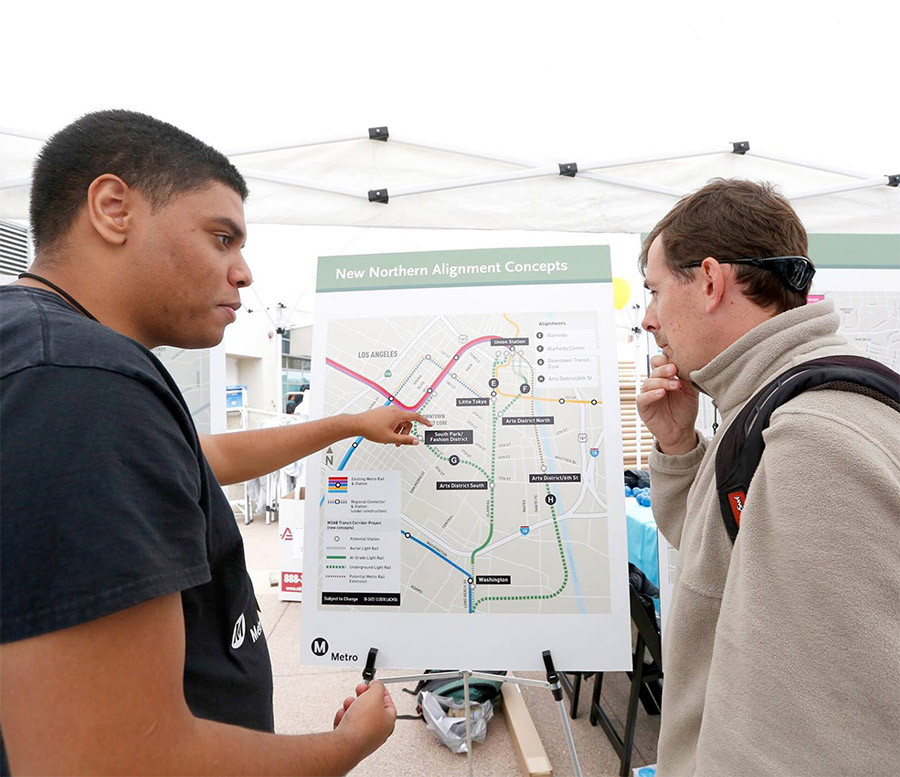

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships