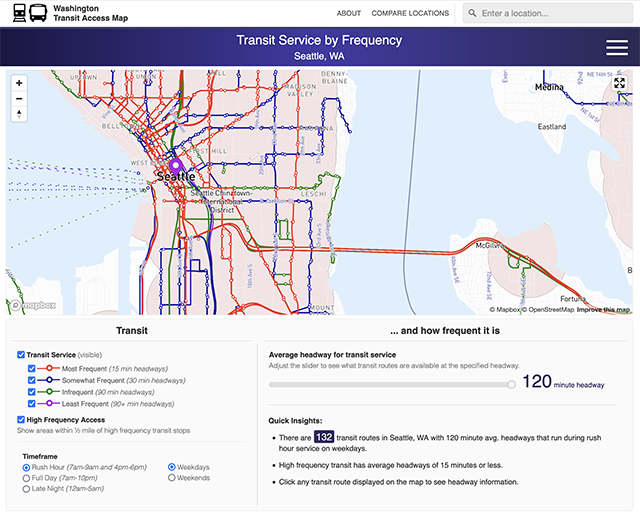

Growth around our transit system, commonly known as transit-oriented development (TOD), generates its biggest benefits when it includes all households and all neighborhoods. It gives residents choices for how to get around, particularly to jobs, and connects them to economic opportunity. It lowers the cost of living by making it easier for households of all incomes to live with fewer cars. It’s good for the climate with fewer cars on the road. And when it includes all types of households, it can break down segregation by enhancing diverse neighborhoods.

But Chicago has failed to capture housing around transit on all sides of the city. Compared to regions with large, legacy transit systems, only ours grew faster away from transit stations than around them between 2000 and 2010. The Chicago Housing Authority Plan for Transformation alone led to the loss of nearly 6,000 occupied units near transit. Many of our transit-served neighborhoods continue to experience distress; the number of people within 10 minutes of the Green Line between Indiana Avenue and Ashland/63rd dropped by 33 percent. And on the North Side, restrictive zoning has made neighborhoods more exclusive. Despite millions of dollars in private investment in the half-mile around Lakeview’s Belmont station, de-conversions and teardowns helped create a loss of 1,234 housing units.

It’s a three pronged problem that demands a three-pronged solution, of which TOD Ordinance expansion is a critical component. It would unlock more private investment to help address the loss of market rate rentals. It would expand the radius of eligible parcels from a short distance from transit to a one-quarter mile and help more neighborhoods stabilize their supply of smaller and family size units. It provides bonuses to help market rate developers meet requirements of the Affordable Requirements Ordinance on site. This is a critical mechanism to deliver units within short distance of transit, so that all households can benefit.

The elimination of parking requirements is a much needed step. The Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT) believes that this makes sense because it’s an unneeded cost. Construction costs $4,200 per spot outside to $37,300 inside, and that stall is not free. It can inflate rent by as much as an additional 12.5 percent. In affordable housing developments, it can be difficult to make those costs work at all. Moreover, the requirements often mandate spaces above the number of cars households near transit own.

The TOD Ordinance will create more market rate investment, but there is more to be done to ensure that neighborhood growth includes all incomes and neighborhoods. As communities become more exclusive, it is the loss of housing for low-income families that is most detrimental and hardest to replace. In gentrifying neighborhoods like Logan Square, inclusionary zoning alone will not fill the gap.

We must ensure that the city targets its housing programs to transit-served areas. We must help our robust Community Development Corporations deliver more units on key opportunity sites near transit. We must take deliberate action to slow de-conversion of 2- and 3-flats into single family homes. And we must accelerate the number of CHA properties near transit. Unlike the City of Chicago, the CHA has a Double-A bond rating that could be utilized toward a more ambitious strategy to add low-income housing near transit. We need this “all of the above” approach to housing affordability to ensure that TOD has an equitable impact on all households and neighborhoods.

We support the TOD Ordinance to help our city grow again. But as we support policies to help the city grow, we need to do more to ensure that it includes everybody.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships