During our recent Chicago Truck Data Portal project, cameras counted 5,159 trucks and buses, 129 pedestrians, and 53 bicyclists in 24 hours at West 41st Street and South Pulaski Road in Archer Heights. Truck count researcher and Urban Resilience Associate Paulina Vaca reflects on how supply chains, as currently configured, cause high truck concentrations. She also writes how supply chain operations harm communities and their residents and what we might do next to make supply chains less toxic and more life-affirming.

There is so much movement in a city like Chicago. Boats navigate waterways, planes trace the sky, the ‘L’ and other trains rush (or crawl) on tracks, and all types of vehicles roll on pavement.

Supply chains are our economy in motion. Yet today’s linear supply chains generate harmful consequences by design, from start to finish... and beyond. Even after products have been made, sent, and used, they produce waste that perpetuates damage to our natural world.

How can we redesign supply chains? Addressing concentration of supply chain facilities in specific areas, altering wasteful or harmful processes, or reforming the supply chain cycle itself, for example by shifting from a linear to a more circular economy are a few possibilities.

In this post, we’ll look at general steps in supply chains. We’ll zoom in to understand how supply chain infrastructure looks on Chicago’s Southeast Side and out to understand negative externalities more globally.

Let’s start with truck transportation

‘Dirty energy’ transportation that burns fossil fuels tied to climate change— from vans to related equipment like forklifts and cranes— makes it possible for materials to flow in supply chains. One critical contributor is truck traffic.

Our Chicago Truck Data Portal, created with Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO) and Fish Transportation Group visualizes medium- and heavy-duty street traffic through select roadways over a day’s time in 2023. We chose roads in frontline communities that are home to immigrants, people of color and those with less income. We also looked at more affluent communities.

Truck pollutants

Tailpipe exhaust from trucks that run on fossil fuels (notably diesel) is the leading local air pollution source from trucks. It causes harms like eye irritation, worsening asthma, and in some cases premature death.

Beyond exhaust, trucks produce dust due to particulate matter from tire friction on the road and uncovered trailers carrying bulk materials. Truck traffic can be an issue of safety and mobility for other road users, causing congestion, noise pollution, and even vibrations on the street and surrounding buildings.

Cumulative impact

We found a stark disparity in truck traffic between communities. In the frontline areas, residents and workers face the brunt of commercial and industrial pollution sources.

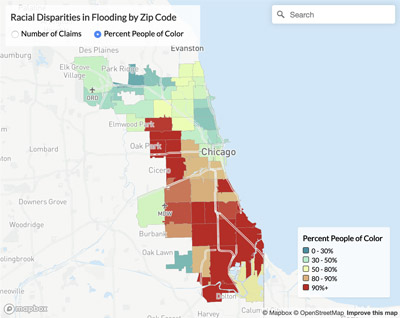

Land-use decisions reflecting institutionalized racism (examples: inner-city highway expansion, urban renewal, and redlining) mean most multi-source pollution hits people in Archer Heights and other communities with predominately people of color, working class, and immigrant populations.

Chicago’s 2023 Cumulative Impact Assessment highlights how frontline communities face multiple negative impacts from other polluters in addition to trucks.

Not all our truck counts are part of a supply chain. Public transit, school buses, emergency services, utilities, moving, and public works like garbage and recycling produce truck traffic, too. But the portal’s video data suggests much traffic was related to the movement of goods in supply chains.

Demystifying supply chains

Thinking about trucks led us to think more deeply about supply chains that are the cause behind so many of their movements.

It’s very, very rare where you can think of an item that gets created or manufactured, grown, and consumed in the exact same place in the exact same time,” says Chris Caplice, director of the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics. “Supply chains span the globe; it’s the piece that ties everything together.”

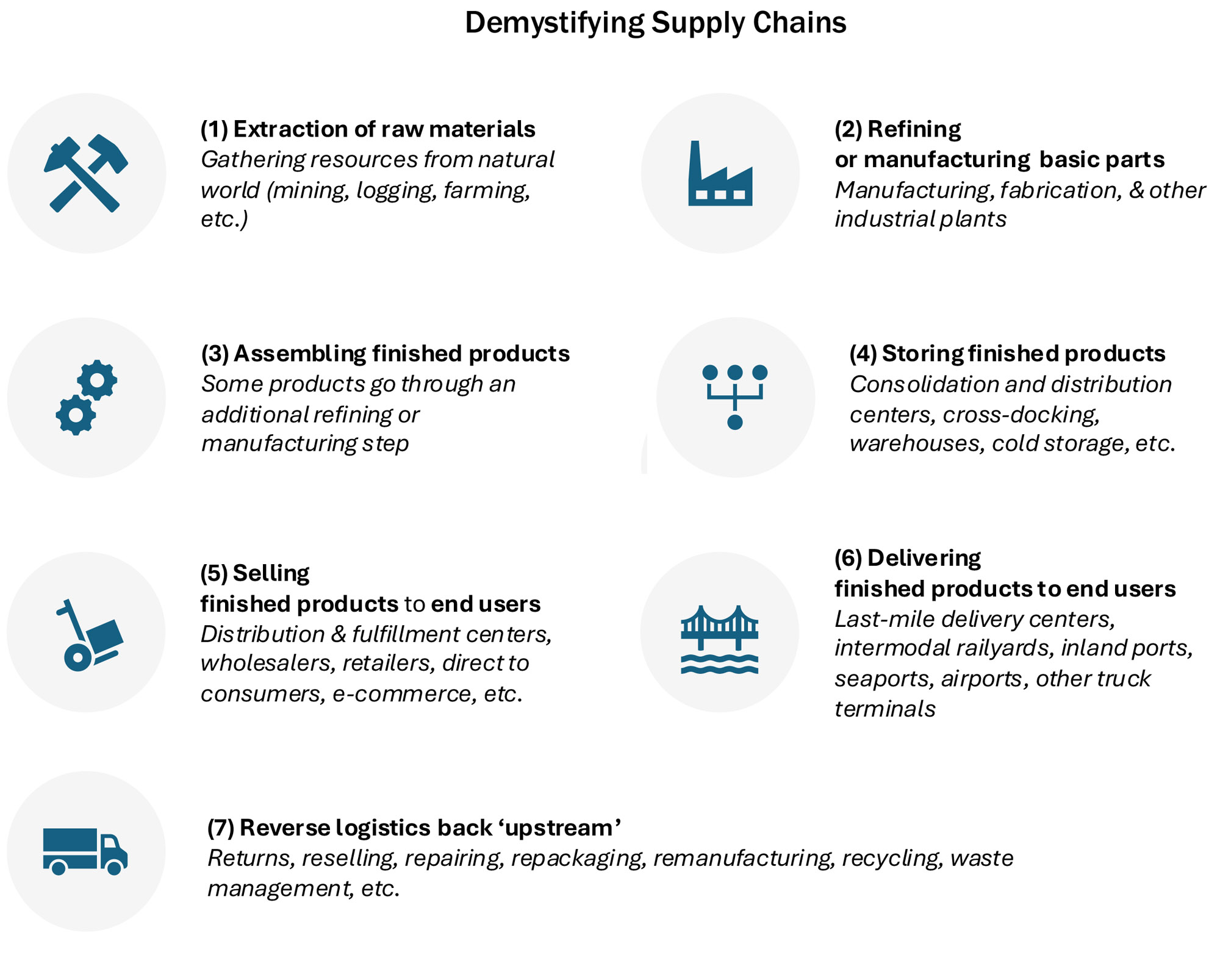

Experts like Caplice describe a roughly seven-step process (see diagram)

Note: Step 2, includes mega-polluting Large Quantity Generators, per USEPA; Step 7, see CA Department of Toxic Substances Control Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities

In supply chains, raw materials flow downstream toward sites for finishing goods, a process of inbound logistics then on toward sale and eventual use, or outbound logistics. Despite its name, supply chains are less of a chain and more of a web that connects product making and delivery.

A geographic flow image of Volvo Construction Equipment illustrates how complex and expansive a single supply chain can be. Worth noting: supply chains are all around us, but supply chain maps like this are difficult to access, whether because of complexity, lack of open-source tracking tools, proprietary company information, or for other reasons.

Sourcemap image accessed via MIT Supply Chain Fundamentals edX course

The Chicago region is home to industries that manufacture product parts and finished goods (steps 2 and 3 from the above section), though much manufacturing and assembly is outsourced abroad to cut costs for corporations.

Chicagoland is also home to plenty of infrastructure that stores and delivers product parts and finished goods (steps 4 – 6, outbound logistics). Chicago is the only place in the Western Hemisphere where the country’s largest goods-carrying railroads converge; in fact convenience as a shipping hub is part of the city’s origin story. Lastly, Chicagoland has waste-management infrastructure that is part of reverse logistics (step 7).

Zooming in

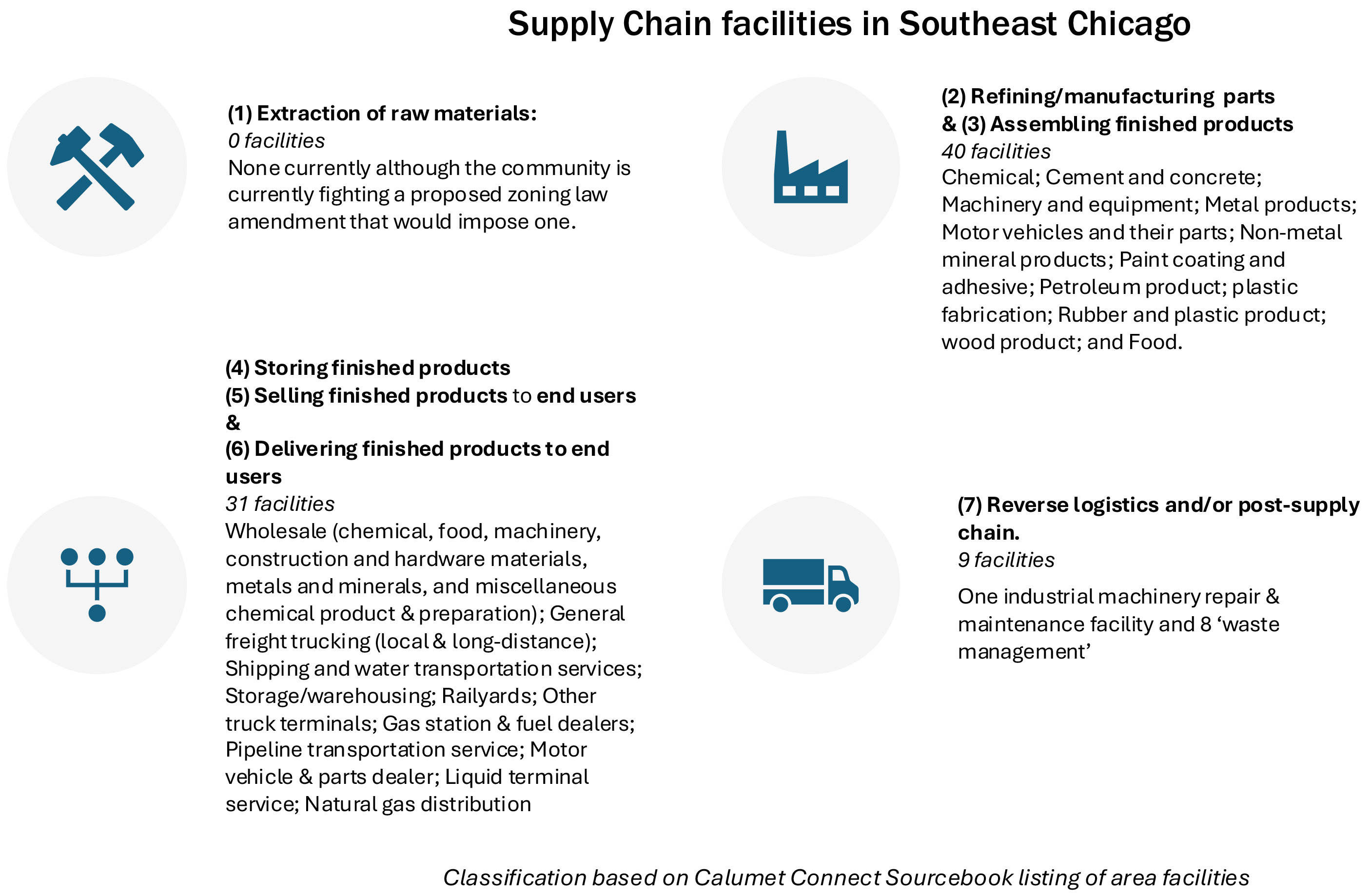

The Southeast Side’s Calumet Industrial Corridor contains Chicago’s largest area of land zoned for industrial activity and is the only place in Chicago zoned for residential buildings and hazardous waste. The Calumet Connect Databook project by Calumet Connect, Alliance for the Great Lakes, and other partners identifies over 90 industrial facilities (based on 2018 data) that seem to fit within supply chain processes.

This intense concentration of supply chain facilities— much like the exceedingly high truck counts in the Southwest side’s Archer Heights— highlights challenges that Southeast side residents face from supply chain production and byproducts.

Negative externalities

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, an economy asks three questions:

- what is produced,

- how to produce it, and

- who benefits?

Every economy has flows of materials, energy, and information. Supply chains are closely connected to these constantly moving flows. To get to sustainable and holistic solutions, we need to untangle root problems.

Supply chains are fundamental to our economy. Their operations also cause pollution (environmental and climate injustices), labor violations, and other infringements on human rights and dignity (social injustices).

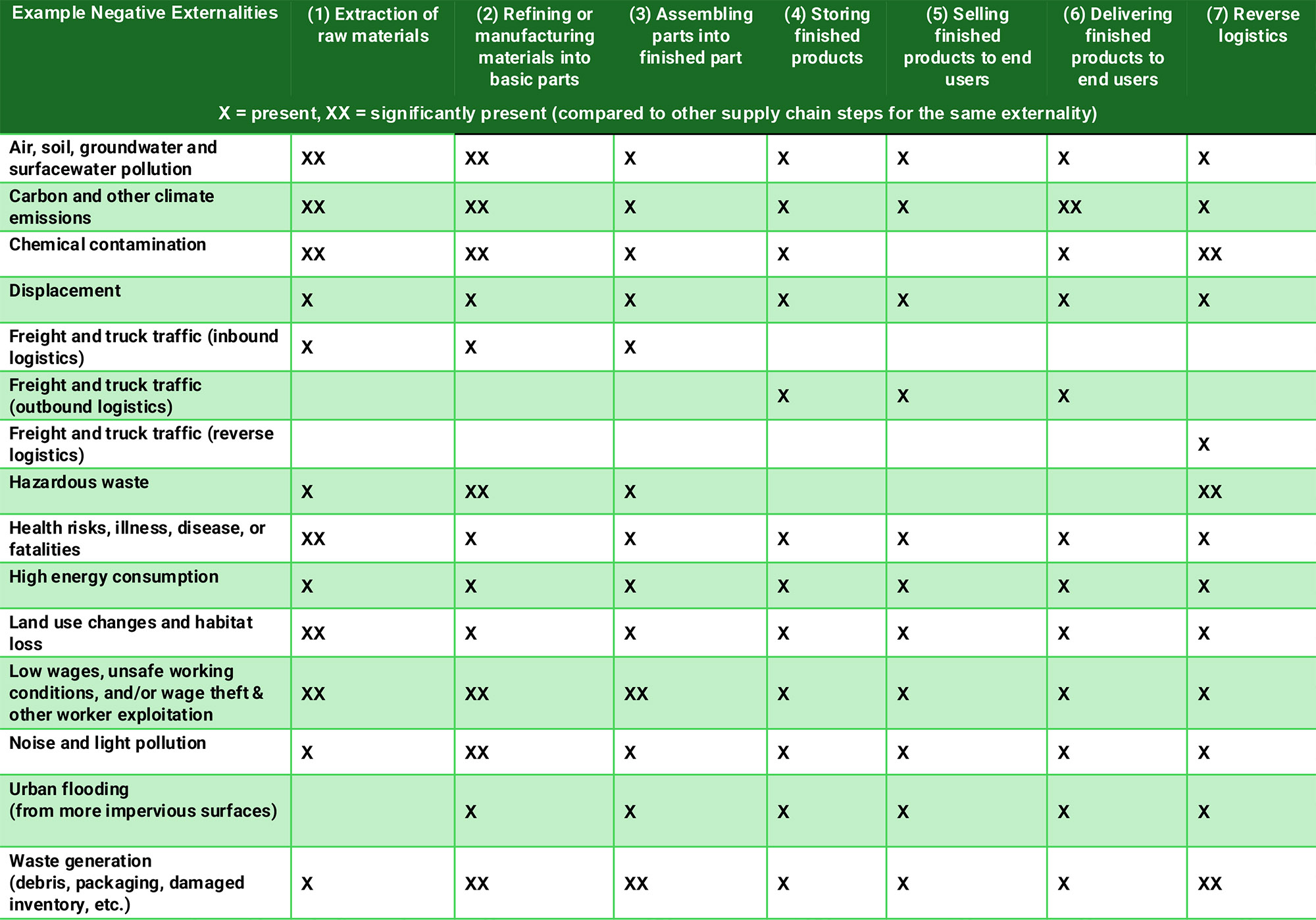

Bad outcomes like pollution are a negative externality: an economic term that describes harmful consequences imposed on someone or something by a business’ operations. Workers and those living or spending time close to supply chain activities, and nearby ecosystems often shoulder much of the burden.Here are some significant examples of negative externalities throughout a supply chain:

The negative externalities notably represent environmental, climate, and labor justice concerns. These injustices are intertwined. As stated in Warehouse Worker for Justice’s ‘For Good Jobs & Clean Air’ report:

“Fossil fuels that power our supply chain are the driving force of the climate crisis, filling the atmosphere with greenhouse gasses, disrupting natural systems, exposing people to sickness and leading them to premature death.”

Optimistically, negative externalities are a choice. Our legal and policy systems offer tools to incentivize better decisions, but meaningful change begins with understanding the impacts and demanding action. The status quo reflects the compromises of past decision-makers, but we have the power to choose differently.

Re-designing supply chains: circular, not linear

Re-envisioning supply chains to include protections for those who live and work where these industrial processes are located—especially in areas of hyper-industrial concentration—is a moral obligation as well as smart policy. Too often in the status quo, advocacy to deny a building permit is one of the few if not the only tools available to residents advocating for their community.

We need other ways to address supply chain negative externalities.

Most supply chains under our current economic system act as a linear economy. Meaning, the flow of materials and goods going downstream ends in waste. It is a “take-make-dispose” or “cradle-to-grave" process.

To attain more beneficial outcomes or positive externalities for people and our planet, supply chains must be re-envisioned. While the current linear supply chain leads to pollution and social injustices, efforts to make it more sustainable within our existing economy include:

- A “cradle-to-cradle” or circular economy, in which we reduce, re-use or recycle waste rather than warehousing it.

- Frameworks like a Just Transition harmonize planetary well-being and a thriving economic system. With a Just Transition, one population’s consumption of goods does not have to cause damage to another.

In addition to re-envisioning systems of production, we can take concrete steps. For example, two state-wide policies under discussion in Illinois to improve air quality are the Advanced Clean Trucks or ACT rule to build more electric trucks (new supply chains) and the Heavy-Duty Omnibus or HDO rule to reduce tailpipe emissions from non-electric trucks.

At the federal level, policies like the Cobalt Supply Chain Act aim to ensure goods like electric vehicle batteries entering the U.S. do not come from child or forced labor in the Congo.

What’s next

These are the sorts of questions we need to consider in re-designing supply chains— whether through more policy making, urban planning, product design, supply chain management, or other fields.

Center for Neighborhood Technology, with Little Village Environmental Justice Organization and other partners, continues to collect and make accessible data in ways to promote more livable built environments.

We’re planning to update our Chicago Truck Data Portal later this year to reflect a new (summer 2024) truck traffic count in Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood. This is because a truck-generating distribution warehouse currently threatens to replace historic industrial buildings in the predominantly Black neighborhood. Data like this bolsters community advocacy for healthy urban life.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships