At this year's Transportation Research Board's (TRB) meeting, twelve TRB committees came together to sponsor a session entitled, "Equity Reframed: Looking Back and Planning Ahead." The focus was to review historical milestones and forecast future opportunities to eliminate systemic barriers to full equity by marginalized communities and to provide more equitable access to transportation services. As a speaker, I had the opportunity to share CNT’s perspective.

Our session discussed how equity in transportation has been defined historically and how policy had addressed equity in transportation since the Civil Rights Movement. Panelists addressed the types of problems that served as the impetus for creation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the Age Discrimination Act of 1975; the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990; Executive Order 12898, “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice” in 1994; the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1994; and major surface transportation bills. Our session also looked to the future: responding to equity issues emanating from technology changes, using policies to advance equity principles, and applying new public involvement techniques and equity performance measures.

My contribution bridged both parts, giving an advocate’s perspective and on the history of equity in transportation. Unfortunately, too many people equate equity with equality. During my presentation, I tried to make clear how equity and equality are defined, giving examples of the difference between the two.

Transportation inequities became clear from my life’s experiences. I remember when the Dan Ryan was being laid out. My community learned about the alignment from stakes in the ground with orange flag ties. I didn’t know it then, but it gave rise to my transportation advocacy and awareness of the inequities in transportation planning and implementation. My story was not unique: across the country, conditions that were occurring on-the-ground gave impetus to advocating for new policies.

During my career I joined other advocates who were addressing inequities and collectively we called attention to disparities in our communities and communities throughout the country. We organized to make changes. Through collective action and coalition building, even as advocates we were able to advance equity by striking down systemic barriers.

Transportation inequities affect communities of color and low-income residents in many ways. To name a few:

- Local quality of life impacts. Transportation affects the health of residents in segregated communities where air and water pollution is often already a problem. Transportation decisions can impact the air breathed, water consumed, and the ability to engage in physical activity, and transportation projects can generate noise, vibration and visual changes impacting sensory and aesthetic conditions.

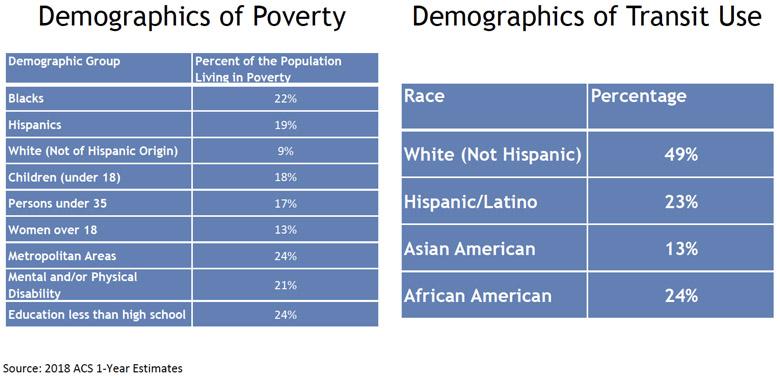

- Accessibility. Transportation projects can either connect residents to economic opportunities or create disconnections. Spatial mismatch – the disconnect between jobs and housing – makes it challenging to find jobs that have viable transportation options. This is particularly true for low-income residents who are not car owners. As shown below, there is a high correlation among African-Americans and Hispanics between being in a zero-car household and poverty. Transportation projects and policies don’t often address these needs.

- Displacement. Many times, displacement from transportation projects – either from the project itself, or the changes in land value that result – causes economic disruption, loss of affordable housing and loss of social cohesion, which impacts the socio-cultural activities of community residents and their quality of life.

- Compounding impacts of safety and security. Transportation inequities take place in communities that are already over policed and under protected, with worse emergency response times than higher-income, majority white communities. Projects sometimes create unsafe situations for more vulnerable residents because pedestrians’ needs are unmet.

- Lack of public involvement. Development, implementation and enforcement of transportation policies, plans, projects and programs have often been done without any public involvement. As a result, communities of color and low-income communities experienced the largest burdens and fewest benefits.

The transportation inequities suffered by minorities and low-income groups are complex. Directly and indirectly, they have had cumulative effects contributing to systemic poverty in communities of color: in 2018, about 20% of Blacks and Hispanics lived in poverty, and had significant transportation expenses. Households in the bottom quartile of income spends about 32% of their income on transportation, and spending on transportation is higher for African-Americans than for whites across income levels.

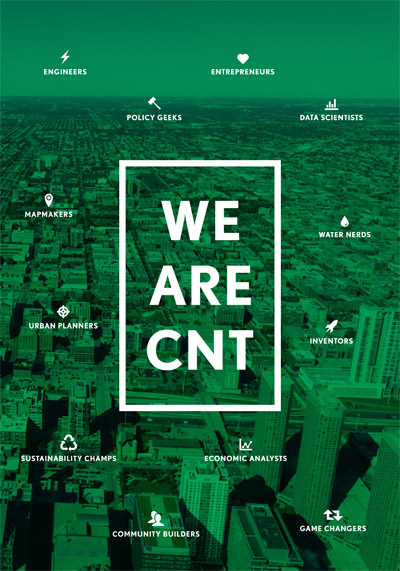

Looking toward the future, I also discussed the impacts of equity in smart mobility, using CNT’s research report on Equity and Smart Mobility as my source. The report dealt with the tremendous disruption being caused by technological innovations: transportation network companies (TNCs), autonomous vehicles, vehicle electrification, the reliance on 5G connectivity.

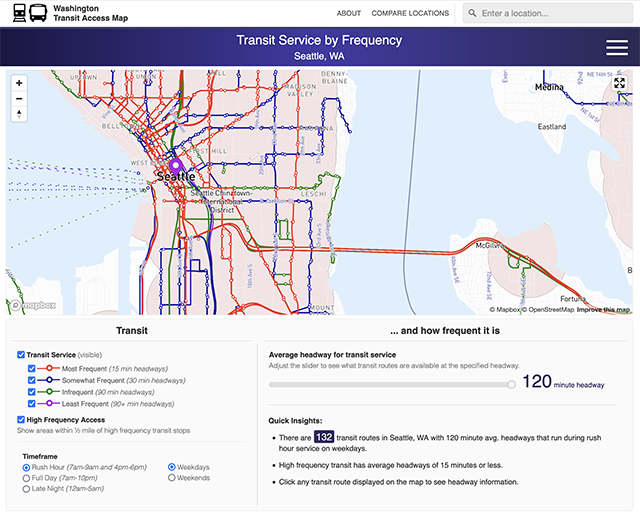

New modes of transportation create an opportunity to improve transportation equity, but we have not taken advantage of this opportunity. In short, our research found that access to new mobility is not equitable. Whether measured by access to carshare or bikeshare locations, or waiting times for TNCs, inequities existed. Further, because access to smart phones and bank products (credit/debit cards) is often required to access smart mobility options, new possibilities for further inequities are emerging.

Recitation of problems is an inadequate exercise without solutions being recommended. To address equity in smart mobility, we must:

- Invest in the most underserved communities.

- Involve people who have been systematically excluded from the transportation planning process.

- Prioritize projects that serve those most vulnerable.

CNT hopes that our research makes a contribution to our evolving understanding of new mobility and equity. Overall, regardless of what transportation innovation comes next, our approach to ensuring it advances equity needs to be informed by history.

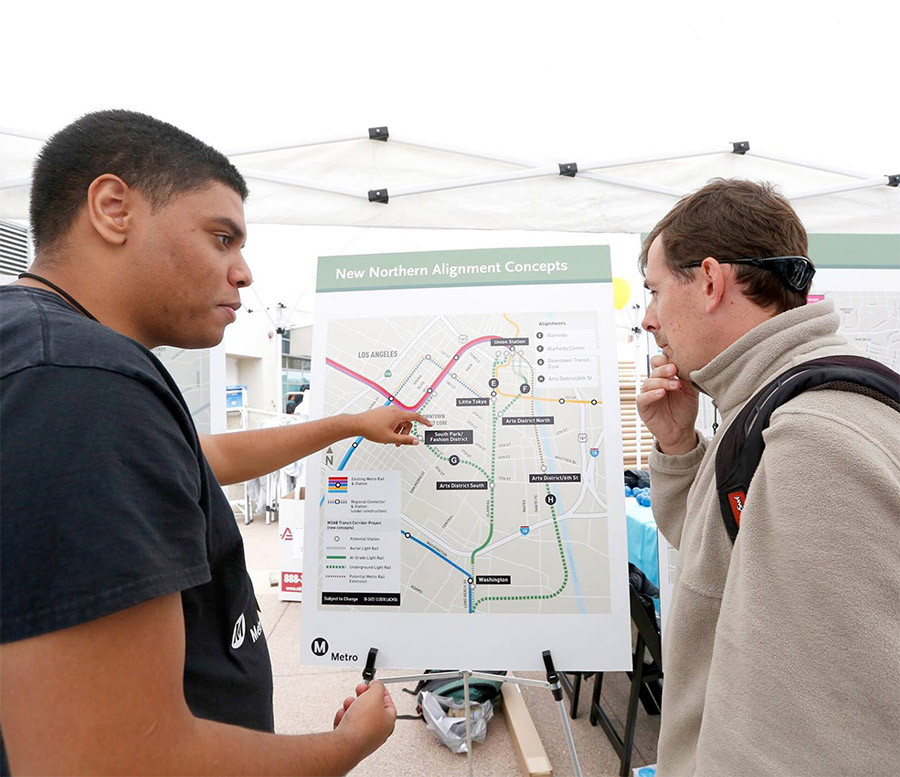

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships