One out of every three spaces. CNT visited the back lots and garages of apartment buildings around Chicago at 4:00 a.m., when tenants are asleep and their cars parked, and found one third of parking spaces empty. This excess parking capacity is a neighborhood affordability issue. Each indoor, underground parking space costs $37,300 to build. Multiply that by all of the spaces in the lot, and the price tag is huge. What if developers applied that money to build more affordable housing instead?

CNT sought to answer this question in our new report, Stalled Out: How Empty Parking Spaces Diminish Neighborhood Affordability, released today.

To find out, CNT interviewed multifamily developers in Chicago and found that when municipalities ask developers to build too much parking, those spaces add time and money to projects. They drive up construction costs and rents for market-rate units. And parking requirements hinder the development of affordable housing near transit because subsidy programs cannot account for the dual price premiums on parking and land.

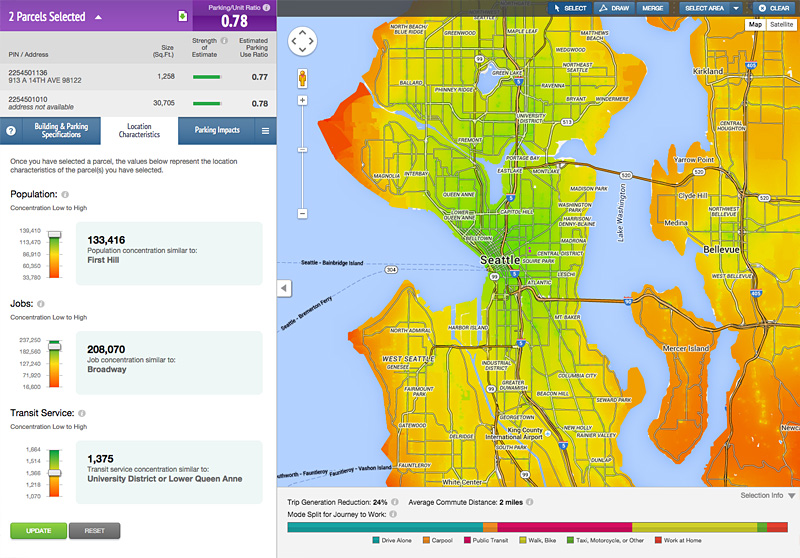

We then applied CNT’s pioneering approach to determining actual parking demand. CNT has conducted research in King County, Washington; the San Francisco Bay Area; and Washington, D.C. To develop our research, our local partners visited parking lots and garages at 4:00 a.m. when most renters have parked their cars and are asleep in bed. Across all three cities, we consistently found one third of those residential parking spots sitting empty. So we decided to take the same approach at 40 affordable and market-rate apartment buildings across Chicago.

Consistent with our research elsewhere, we discovered that:

- The supply of parking exceeds demand. Buildings offered two spots for every three units. In reality, they only needed one for every three.

- As parking supply goes up, much of it sits empty. Apartments with fewer spaces saw a greater percentage of their parking used.

- Apartment buildings near frequent transit need less parking. Buildings within ten minutes of a Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) train stop had one spot for every two units. Even then, one third of their spots sat empty.

- The opportunity costs add up. If we applied these numbers to a 100-unit building near the CTA system, the empty parking spaces would add up to $825,000 in wasted construction costs.

Municipalities typically mandate at least one parking space per new housing unit, even for buildings near transit stops. But with so many costly parking spaces already sitting empty, the time has come to rethink parking as a resource that needs to be managed so that supply and demand are more in sync. If that happens, parking costs decrease and the supply of market-rate units expands. Affordable housing developers can stretch subsidies further. And land can be used more efficiently for retail, services, and amenities, making it easier to get to them without driving, reducing demand even more.

There are many ways this can be done.

Municipalities must right size their parking requirements to reflect the real demand for off-street parking near transit and create incentives to pass on the savings through affordable rents. For example, the City of Evanston recently reduced parking requirements around transit to help developers follow the Inclusionary Housing Ordinance. Upzoning bonuses like these reward developers to follow inclusionary zoning rules and build more compact communities that include units for everybody.

Developments like 1611 W. Division can get away without any parking at all, if they include access to amenities like transit, car sharing, and bicycle sharing. That development, which sits by the CTA Division stop, includes only one parking spot -- for a car share vehicle, for which residents receive a discounted membership. It also has access to Divvy bike share and three CTA bus lines. This building leased up in less than six months.

Often times, though, well planned developments lose steam due to neighborhood concerns. And with the on street parking situation in neighborhoods like Edgewater, who can blame them? That’s why good data, like the data provided in our report, can help residents understand the difference between the on street parking crunch and the surplus in garages and lots. CNT and the Lakeview Chamber of Commerce tested this idea last year in developing a white paper on housing and transportation trends in the neighborhood.

How can affordable housing developers and non-profits utilize these rules and concepts, and work with residents on equitable transit-oriented development (eTOD) projects with fewer spots and more spaces?

That’s the next step.

On May 19, we’re organizing the first eTOD Laboratory with Enterprise Community Partners. Stay tuned for more information on our website.

There’s a lot of wasted value in empty parking spaces. Together, we can reduce that wasted space and pass on the savings in more affordable units.

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships

Strengthening Transit Through Community Partnerships